A fourteen year old boy who lives in America, but was vacationing in Mumbai came to me a few days ago. Let us call him Raj (name changed).

A footballer at the inter-school level, he was playing the sport for the last eight years.

Raj came with a history of an injury during a game that he played a month ago for his school. He was seen by the therapist from his team, but was now in my clinic because his parents were worried about an abnormal swelling that they saw in front of the knee.

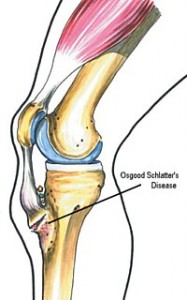

Actually what Raj had was a very common “Growing-Up” injury, which happens mostly in active adolescent boys. It is called Osgood Schlatter disease.

Muscles are attached to bones by strong bands (tendons), and as the muscle contracts strongly, the tendon pulls on the bone resulting in a movement at the joint. When a big growth spurt takes place (increase in height), sometimes bones grow faster than the muscles. While the length of the muscle is trying to catch up with the length of the bone, the shorter muscle ends up exerting a greater force than the tendon attachment can bear.

The Quadriceps is a four headed large and strong muscle in the front of the thigh and is attached by a relatively small tendon just below the front of the knee. In active adolescent children (Boys more than girls), this tendon sometimes pulls too hard on its attachment and dislodges a part of the bone there, causing pain, swelling, and a visible “bump” in front of the knee.

If given adequate rest and treatment, the pain and swelling usually resolves itself (The bump sometimes stays on, but it is not significant in sporting performance later). What usually happens though is that in severe cases (like this boy who came to me) a year or two of their sporting career is lost due to pain and enforced rest.

Can this be prevented? Maybe not. The small repetitive injuries that the strong pull of the muscle is causing cannot be detected early enough, and more often than not it is diagnosed only when significant damage has already occurred.

But here is what I feel very strongly about. Should children in sport not be regularly screened for growth spurts, tight muscles (something as important as the Quadriceps), and many other factors that commonly contribute to injuries? Should their exercise plans not be based on such findings?

The case in point (Raj) had such short Quadriceps that when he lay on his stomach, his knees could only bend to 90 degrees, whereas normally the heel should almost touch the buttocks.

He was with the team for eight years, he was a valuable member of the team, and was in their care during his growth spurt. Nobody noticed that he had such tight Quadriceps.

I do not know for certain and cannot prove that a good screening and concentrated stretching plan could have prevented his injury. But I do believe that perhaps it could have been prevented or at least its severity lessened.

This is not an isolated case, most children in sport are not screened with care often enough to predict and prevent injuries. Most children in sport are not important enough to get much individual attention, and almost none get individualised prehab exercises.

The sad consequence is that we lose valuable sporting talent, because the age that these injuries occur at is also the most crucial stage in their professional life: many talented children, if not adequately backed by parents and support groups, eventually give up on their chosen sport and pick another career.